The real shock was when we discovered that Saber was sick on October 14, 2019.

We tried to take him abroad for treatment, but unfortunately, there were obstacles everywhere. We were Palestinians from Syria, fleeing war and dealing with displacement. It was so difficult that we even thought about going back to Syria, but that meant that Saber had to go back into the army. We knew that it would take a long time until they believed that he really was sick, and we couldn’t afford to wait because we might lose him to liver cancer.

Saber passed away after battling cancer for a short while, but during his life, he had always been an ambitious young man who was forced to suffer war, displacement, and unemployment for three years until he was finally granted a scholarship to study nursing, as he had always dreamed.

He used to be a helping nurse ever since he was still in Syria, before even studying at a university. Saber had a passion for helping people and doing benevolent work, and even when there was heavy shelling over our area, he was out there doing his best to help others. He was very kind, loving, and helpful, which is why he chose nursing in the first place.

Sadly, Saber passed away barely three months before his anticipated graduation. A ceremony was held at his university in his memory and he graduated postmortem. It was a bitter-sweet event without him.

When we found out about his illness, we tried to communicate with the Embassy and many other authorities in order to take him abroad for treatment, knowing that treatment possibilities were much higher in Europe, including giving him a liver transplant. However, we couldn’t do that, perhaps because we were Palestinian, or maybe because we had no money. Fate wasn’t on our side…

*********

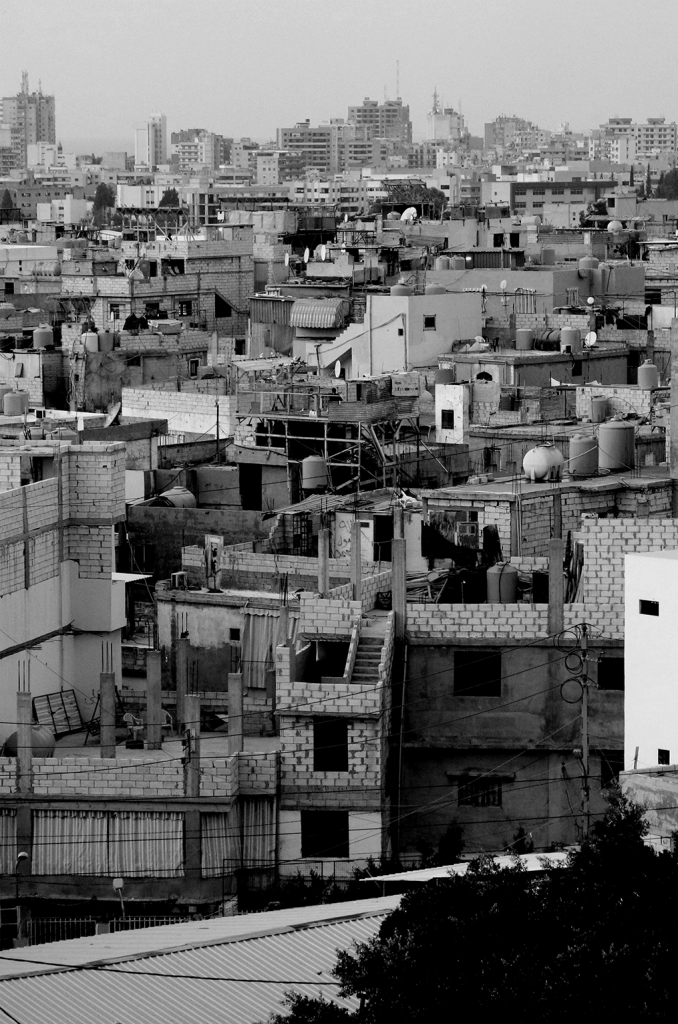

Saber had learned how to give shots during the war and how to take care of people. He used to provide blankets and food for the displaced people in the mosques. Yarmouk camp was opening its doors to people as the rest of Syria was shutting down due to war, and Saber was one of those people whose heart was always open to everyone. He enthusiastically helped anyone who took refuge inside schools and nearby mosques. When the camp was under siege and our house was bombed, Saber evaded eminent death and, by unbelievable chance, was able to flee Yarmouk to Qudssaya. He struggled a lot to get to Al-Jroud, Al-Qalamoun and Khan Al-Shih in Syria, before finally leaving Syria to Lebanon.

In order to travel to Lebanon, Saber had to pay a fee of five thousand Syrian pounds in order to postpone his obligatory military service. When he arrived in Lebanon, he got stuck in the country, having to stay because Palestinians weren’t allowed to leave the Lebanese borders, and at the same time, fearing to return to Syria because of obligatory military service. After three years of poverty, displacement, terrible living conditions and much suffering endured in Lebanon, Saber was able to pursue his education at the university with the help of a scholarship. Although that covered his university fees, he still needed to save some money from his food and transportation allowances. Saber used to walk at least 2 kilometers every day to and from his university. He even used to wear the same clothes on most days, but he didn’t care much about that, as his only concern was to graduate with the degree he had wished for.

Indeed, we were all very proud of him for pursuing his dream as a nurse. That was until that fateful day in October 2019, when we found out that he had liver cancer. We tried to save him, but we were defeated by the circumstances…